August 8, 2025

Civics

Striking parallels link witch-hunt falsehoods to today’s online misinformation.

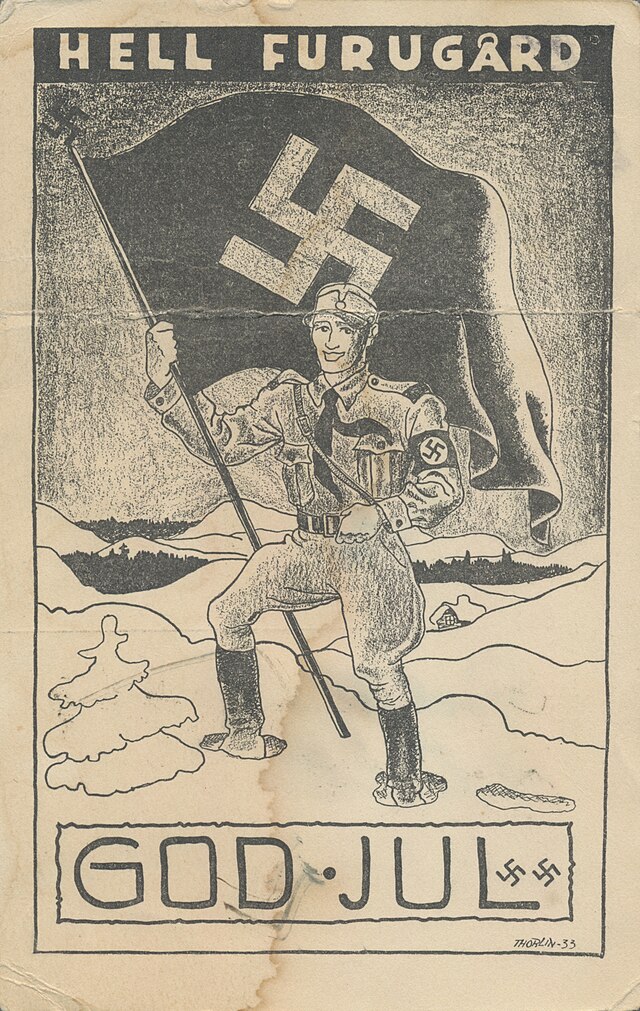

Witches being hanged in 1655 From Ralph Gardiner's England's Grievance Discovered in Relation to the Coal Trade

Julie Walsh says that we have been here before. Writing in The Conversation, she draws stark parallels between the witch hunts in early modern Europe (1400–1780) and today’s misinformation crisis on social media. Both were fueled by new media technologies—the printing press then, social platforms now—that enabled rapid spread of sensational and harmful content.

The press circulated works like the Malleus Maleficarum (“Hammer of Witches”), which entrenched stereotypes about women and legitimized witch hunts. Today, algorithms amplify misinformation regardless of accuracy. In both eras, skeptics challenged falsehoods but struggled to be heard over emotionally charged narratives.

False stories that align with fears or beliefs, she says, gain power through repetition, whether in print or online. Financial incentives also played a role: publishers profited from witch-hunt literature, while social media companies and individuals profit from viral misinformation today.

"The witch hunts offer a sobering reminder that delusion and misinformation are recurring features of human society, especially during times of technological change and social upheaval. As we navigate our own information revolution, those early skeptics’ questions remain urgent: Who bears responsibility when false information leads to real harm? How do we protect the most vulnerable from exploitation by those who profit from confusion and fear?

"In an age when anyone can be a publisher, and extravagant tales spread at the speed of a keystroke, understanding how previous societies dealt with similar challenges isn’t just academic – it’s essential."