I’m Mitch Anthony. By day I'm an idea wrangler for hire. Writing and editing Love & Work is my hobby. I think of it as my knitting —to relax, I weave disparate ideas together in the hope we might see things we hadn't noticed before. Photo by Matthew Cavanaugh.

Why

We are not hungry for information—we are starved for synthesis, for the perspective to connect what we know. We have what we need to create a better world. We just haven't put the pieces together yet.

To imagine a different future is not only an act of survival; it is the foundation of personal renewal and social transformation.

What

Love & Work is a catalog of resources and tools that support a simple premise: humans can learn to live as fulfilled citizens with this remarkable planet we call Earth. This belief rests on the recognition that, like the universe itself, humanity is always evolving—that human consciousness continually unfolds toward greater awareness, collective intelligence, and creativity. We are a learning species. While much remains to be discovered, the evidence shows we are, in fact, learning.

At first glance, today’s news might suggest that living in harmony with one another and with our environment is a hopeless ideal. But this is not a news channel. My interest lies in gathering evidence of what we are learning so we can pause to notice and appreciate it. Taken together, these learnings form a focus that, to me, looks a lot like good news.

Each of the articles published here was originally posted on my weekly newsletter of the same name. The letter curates ideas across nine primary themes:

Radical Hope: I foreground hope as an active, agency-based stance—not naive optimism, but a call for responsible, participatory effort in addressing our shared challenges.

Creativity and Courage: Creativity has defined my career, and I know it to be a powerful tool for solving complex problems. Yet in a world where many cling to the familiar, genuine creativity requires courage.

Systemic Change: Systems built on endless growth, disconnection from nature, ego, and greed cannot and should not be preserved. I hold deep skepticism toward “business as usual” and instead embrace the need for entirely new visions of futures that might truly work.

Systems and Design Thinking: Systems thinking invites us to slow down, widen our perspective, and notice patterns—how fear loops into distrust, how care ripples into resilience. It reminds us that small, intentional shifts can move the whole. Design thinking complements this by showing that beauty and utility can coexist, that attention to detail is care for people, and that thoughtful changes can open wide new possibilities.

Education and Lifelong Learning: If every child had access to education that met their unique learning style, cultivated systems literacy, and promoted ethical responsibility, we might achieve peace within a generation. Is such an idea more far-fetched than attempting to colonize Mars? Learning is a lifelong practice—essential both for personal growth and for creating communities that can adapt and thrive.

Ecological Wisdom: The living world demonstrates how systems thrive—through diversity, interdependence, and constant adaptation. Cooperation creates resilience, and form follows relationship. We can learn a lot from these lessons.

Community, Cooperation, and Justice: Many of these writings explore how individual and collective agency, cooperation, and reimagining social, educational, and economic systems can foster dignity and well-being. When people gather with openness and imagination, something larger than any one of us emerges: a shared intelligence, a new creativity.

Democracy and Agency: Democracy is an ongoing experiment, and at present it is faltering. To endure, democracy must be rooted in hope and agency—both antidotes to the cynicism and despair that undermine civic life.

Personal Development and Responsibility: Collective change begins in the smallest gestures of daily life. Each choice, each act is a seed. When we tend our own actions with awareness, we help shape the larger patterns around us. Transformation starts within, then ripples outward.

Finally, an important note: what you see here today is not what you will get.

This draft is my first attempt to replant just a very few of the ideas originally posted in the letter in one place. You and I are seeing what these ideas look like together for the very first time. I recognize that without additional editorial direction that they can appear to be overwhelmingly scattered.

This is a work in process. Over time, I expect to edit, curate, and group postings more intentionally. But I have to start somewhere. I've still got thousands more articles that I've dug up from MailChimp and stuffed into pots, and they're all waiting to be replanted. My first task is simply to get them into this new ground. Then I'll start moving them around. Slow and steady wins the race.

Who

Emily Miles

Emily Miles designed, built and maintains the site. Emily started out as a mentee. She was running the one-person marketing department for a friend’s teaching and community-building business, and he asked me to help with branding. Emily is a very quick study, and she quickly became a key collaborator and co-creator with me. Her skills span web design, content strategy, and information architecture—but what sets her apart is her eagle eye. She sees from a very high level, helps name what’s emerging, and can then manage the execution with thoughtfulness and care. Learn more.

Rich Roth

Rich Roth is our data wizard. There are lots of people who can build you a website. But if you’re launching something complex—an ISP, a sprawling digital archive—Rich is the person to call. In my case, I had more than 4,000 news stories spread across 450 email newsletters, all living on MailChimp. I say “had,” because now they’re on our own server and can be repurposed automatically as individual posts. That’s thanks to Rich. It was a huge job but he did it without breaking a sweat. You can read his bio and personal blog here, and learn about building the really big sites here.

“Make the drummer sound good.”

— Thelonious Monk

Search and Discovery

The catalog’s design is built around navigation. Ideas are grouped into nine main categories, always visible at the top of every page. Click on any category, and you’ll find a dedicated page of stories gathered under that theme.

The landing page features the eight most recent newsletter issues, with the latest at the top. Within each newsletter, every article is tagged with both a main category and a subcategory, which helps organize the archive. Over time, I am also adding tags—an extra layer of context that allows you to follow your own paths.

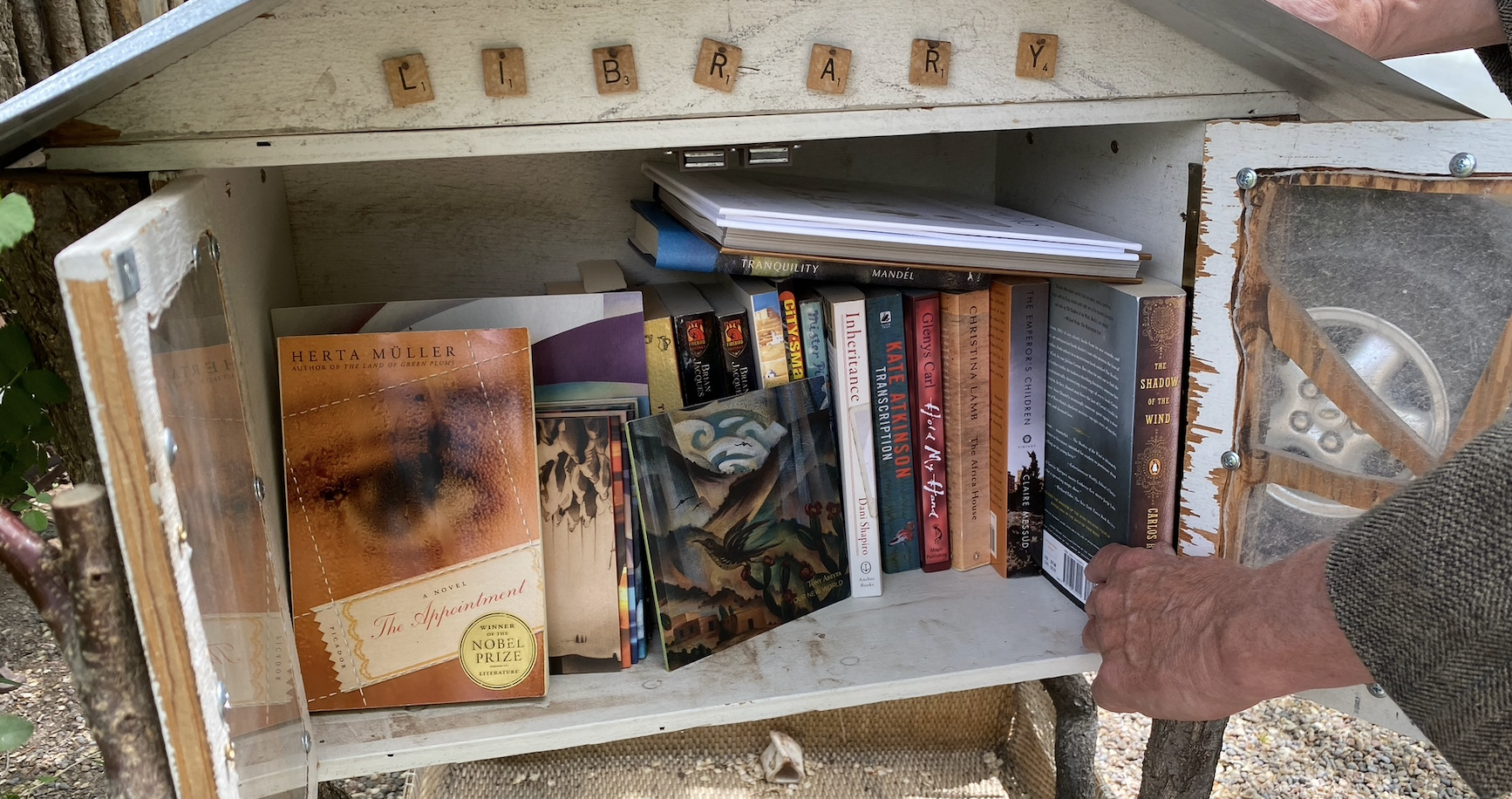

The experience I’m aiming for is one of wandering through a good second-hand bookstore. By browsing, you might stumble across something unexpected, or notice connections that shift how you see things. My hope is that these discoveries feel serendipitous and surprising, yet still easy to find again when you need them.

Information Wants to be Free

In 1984, at the first Hackers Conference, Stewart Brand famously said, “Information wants to be free.”

What he actually said was a little more nuanced: “Information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other.”

He’s right. Publishing information is cheaper than ever. But it still takes a lot of time and effort. And in a era where journalism is fragmented, underfunded, and often distorted by algorithms, the real challenge isn’t making information free—it’s making it trustworthy, meaningful, and worth people’s attention.

So, after nine years of publishing weekly letters without asking for as much as a tip, later this fall I am going to introduce a pay what you can/what you want option.

Stand by.

"Self interest is of the past.

Common interest is for the future."

— David Attenborough

Radical Hope

The philosopher Jonathan Lear introduced the term radical hope in his 2006 book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. Drawing on the story of Plenty Coups, the last great Chief of the Crow Nation, Lear describes a kind of hope that looks forward to a good we cannot yet imagine from within a collapsed cultural framework.

When a culture breaks down—not just losing practices, but losing the very capacity to make sense of life—its familiar ideas of goodness, fulfillment, and meaning dissolve too. The future becomes radically unknown. There is no blueprint, no shared language to describe what a “good life” would look like.

Radical hope is a leap into this unknown. It looks ahead to a future that cannot yet be fully grasped because new values, new forms of life, and new sources of meaning have not yet emerged. As Lear puts it, it “anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it.”

Many others recognize the role hope can play in creating alternative futures:

William Sloane Coffin saw hope as a refusal to despair—a force that motivates action and transformation by confronting reality and investing in possibility. “Hope," he said, "arouses, as nothing else can arouse, a passion for the possible."

Rebecca Solnit describes hope as an urgent, active stance that is essential for social change. “Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency. Hope should shove you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth's treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal... To hope is to give yourself to the future—and that commitment to the future is what makes the present inhabitable”.

Joanna Macy framed hope as a creative and courageous way of engaging with life, springing from our deep connection to the world. "Active Hope is a readiness to discover the reasons for hope and the occasions for love. None of these can be discovered in an armchair or without risk."

Ernst Bloch defined hope as a collective orientation toward transformation and a more humane world. “The concept of hope captures the universal anticipatory drive in human and non-human world—as permeated by futurity”.

Bloch saw hope as the engine of change. It empowers people to resist, to organize, to demand accountability. Authoritarians understand this, he said, which is why they work so hard to extinguish hope itself—by making the present feel inevitable.

Radical hope, then, looks forward to a good we cannot yet imagine from within a collapsed cultural framework. It serves as a shared language for envisioning what a “good life” might be. Rather than clinging to lost structures, radical hope searches for sites where love—or life-affirming value—can re-root once new conditions emerge. Radical hope is a refusal of despair—an urgent, active stance essential for social transformation. Radical hope is the engine of change.

"Hope is a state of mind independent of the state of the world. If your heart's full of hope, you can be persistent when you can't be optimistic. You can keep the faith despite the evidence, knowing that only in so doing has the evidence any chance of changing. So while I'm not optimistic, I'm always very hopeful."

— William Sloane Coffin

Backstory

Born in 1953, I came of age during a brief period in American history when joining the counterculre was a realistic career option.

Mass media outlets like Life Magazine featured communes on their covers. People wore buttons that said, "Turn On. Tune In. Drop Out." Best-selling books like The Greening of America examined the failures of the "Corporate State" and the systemic causes behind them. And a robust alternative media movement informed me that cultural renewal wouldn’t come from institutional reform or violent revolution—it would emerge through profound shifts in individual and collective consciousness.

When I was 17, I had two experiences that would shape the course of my life.

I took LSD. From that moment on, I saw that everything—ecosystems, people, economies, organizations, cells, molecules—was interconnected. I began to understand life not as a series of isolated events or linear chains of cause and effect, but as a dynamic web of relationships, patterns, and systems.

I also discovered The Whole Earth Catalog. In the words of its founder, Stewart Brand, the oversized quarterly “aimed to provide education and inspiration in the form of curated tools, ideas, and books that could help people take control of their lives and participate in shaping the future.”

Mixed with the cultural zeitgeist that promised that I could be a part of making a brand new world, this made a tasty potion. I drank it lustily. This was going to be fun. The rise of DIY culture meant individuals could act at planetary scale. One person with the right tools, networked with others, could influence energy use, food systems, or media. Technology would not only amplify muscle and mind, but also reshape consciousness. New media could become prosthetics for imagination, changing how humans sense their place in the cosmos. The planetary photograph from Apollo already revealed Earth as whole and fragile. The vision: human societies maturing to become stewards, aligning industry with biosphere cycles, treating the planet not as resource but as co-creator.

That was then. Half a century later, it's easy to see that the Age of Aquarius is just that—an age. Its great transformations won’t fully unfold in my lifetime. So in the fall of 2016, I began writing a weekly newsletter, anchored in beliefs I’ve never let go of. I can still picture humanity learning to think in centuries rather than election cycles. I still believe our institutions, infrastructures, and even our cultures can be redesigned with durability, responsibility, and beauty at their core. But, as Tom Waits reminds us in Dirt in the Ground: “Hell's boiling over, and heaven is full. We’re chained to the world, and we all gotta pull.”

Over time, I realized that the newsletter format had its limitations. As a medium, it lacks staying power—most ideas vanish from memory just days after publication. So, I built this website as a 21st-century catalog: a curated, evolving resource of tools, ideas, and books that endure.

My hope for Love & Work, both the newsletter and the catalog, is that they help people see where they can pull.

The Journey is the Destination

I welcome your feedback. What’s working? What’s not? What would make this site more useful to you?

Let me know.